Rashad Farmer: A son, a father-to be, a murder victim

Once a week, Renee Whitfield releases heart-shaped balloons in memory of her son, Rashad Farmer, who was fatally shot last July.

Listen to an audio version of this story

In the St. Louis region, 2015 was one of the bloodiest years since 1995. Just within the city limits, 188 people were killed over the 12 months.

Headlines quickly appear, but each death creates a void for a family, a system and a community. It’s impossible to quantify the full price that gun violence takes each year, but you can start with the story of just one: 23-year-old Rashad Farmer.

LaQuita Clark ties balloons to a tree planted at Barrett Brothers Park in memory of her boyfriend and son's father, Rashad Farmer.

A mother’s grief

When Renee Whitfield got the call that her eldest son had been shot, she didn’t believe it. They had just left each other: She came home from work, Rashad had offered to run an errand for her, but she decided to go herself. Half an hour later, the devastated voice of Rashad’s girlfriend shattered her world.

Whitfield called every relative she knew in north city, jumped in the car and started driving to the Wells Goodfellow neighborhood—not knowing what she would find.

“I felt like I failed him. Like I wasn’t there to protect him,” said Whitfield, 43.

When she arrived, her sister told her that Rashad had died at the scene. Whitfield remembers falling to the ground, screaming.

“It felt like a part of me had left my body. I wanted to go to him and hold him, but they wouldn’t let me.”

Whitfield related all this many months later, on a sunny afternoon in a quiet suburban neighborhood in north St. Louis County.

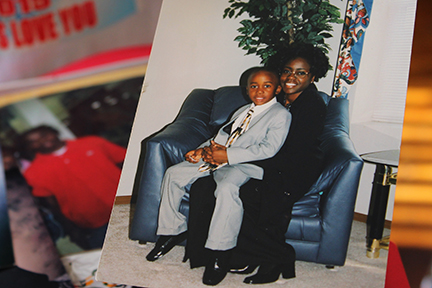

There, Whitfield’s living room is full of tributes to the son she lost on July 14, 2015. A poster has dozens of photographs, and a life-size cardboard cutout of him stands behind the couch. When she met with reporters, Whitfield wore a T-shirt that read, “Rest in Heaven—We Will Always Love You,” with her son’s photograph on the front.

"I knew that he was proud to be a big brother."

— Renee Whitfield

“I had my son at 19; we were best friends because we grew up together,” Whitfield said. “He was a wise soul.”

Almost a father

At 23, Rashad Farmer was on the cusp of so many of the classic milestones of adulthood. He and his longtime girlfriend were waiting on the arrival of their first child—a boy. The couple had just found a house where they could move in together.

His mother remembers him as a gentle presence, with a slight frame, an easy smile and dreadlocks down past his shoulders. Rashad graduated from Riverview Gardens High School in 2010 and studied business management at Lincoln University for a year, before moving back to St. Louis. When his younger brother, Truly, was born four years ago, Rashad helped take care of him. He worked for a temporary staffing agency, loved dancing and the artist Future, and always made it to family events, Whitfield said.

“Every time I look into Rashad’s son’s eyes, it hurts me knowing he won’t have a father. Especially because Rashad would have been such a good father,” Whitfield said.

His son, Rashad Jr., was born on November 11, 2015.

On that July day, the couple had stopped at his girlfriend’s grandmother’s home in north St. Louis. Rashad stayed in the car while she went inside.

As of this writing, there have been no arrests in Rashad’s case, and police have not established a motive for the crime. Family members believe the shooter mistook him for someone else.

In that way, his death is similar to many of the other 187 homicides in St. Louis last year. Including Rashad, 94 victims were between the ages of 20 and 29. The motive remains unknown for more than half of the cases. One hundred forty-eight victims were black, according to the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. And Rashad died in the Wells Goodfellow neighborhood, one of three city neighborhoods to witness more than a dozen homicides in 2015.

An uncle’s voice

But Rashad’s death is also unique. His uncle, Jeffrey Boyd is the alderman for the 22nd Ward, which includes the block where he died. He has spoken out, but Boyd said he has avoided using his political power to influence the investigation in any way.

"Sometimes you want to make a difference…it's a hard road to travel."

— Alderman Jeffrey Boyd

“I was extremely frustrated,” Boyd said. “You work so hard for the community, you want to be this do-gooder, then it happens to you and your family. But of course it certainly speaks to the fact that no one’s immune. You could be the best advocate for Put Down the Pistol or against gun violence and then it could happen to you,” Boyd said.

Boyd and his wife grew up in Wells Goodfellow, and moved back in 1990 to raise their family. Shortly after the shooting, his 16-year-old daughter started to talk about how she didn’t want to live there.

“When your kids start to be frustrated and don’t really like their living environment, it hurts,” Boyd said. “She’s never really said anything like that until this happened.”

The ritual of homicide

Renee Whitfield's 4-year-old son, Truly, releases balloons in memory of his older brother, Rashad Farmer.

A friend of mine says it this way: Homicides have become so common in St. Louis, it feels like a ritual. A memorial of balloons and stuffed animals goes up at the scene. The family raises money for a funeral. T-shirts are made. Life goes on, but for the family, time stops.

On Mondays, Whitfield buys a dozen red balloons and drives to Barrett Brothers Park, just a few blocks from where Rashad was shot.

As Whitfield passes balloons out to family members, they say a quick message, and release them.

“I love you big brother!” calls 4-year-old Truly.

The park has 30 saplings that were planted in honor of St. Louis homicide victims back in October. Rashad’s has a stuffed monkey perched in its branches. Whitfield said she hopes to add a small, concrete memorial soon and start up a foundation in her son’s honor.

“Every day it just hurts … people that are committing these acts out here don’t even realize what they’re doing. You know? They don’t understand that you’re destroying lives. Destroying families because of your ignorance,” Whitfield said.

Imagine that destruction multiplied by 188. Multiply that again by every major metropolitan area in the country. And that figure only represents homicides, not the victims who survive or the people who take their own lives.

"This is something I look forward to…to give me some type of strength…"

— Renee Whitfield

Here, in a cold January twilight at Barrett Brothers Park, it’s dark as we head back to our cars. Shots ring out a few blocks away, out of sight. It’s time to go.