The St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners - A brief history

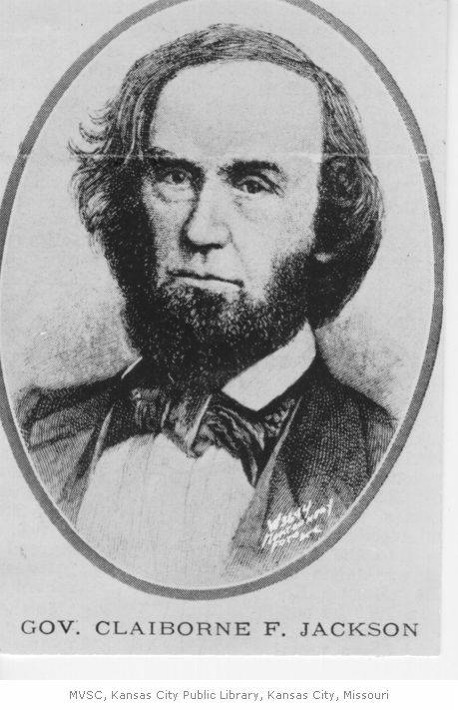

Though Missouri never seceded from the Union during the Civil War, sentiments throughout much of the state were strongly sympathetic to the Confederate cause. In fact, in April 1861, Gov. Claiborne Jackson refused President Abraham Lincoln’s demand to call up the state’s militia, sending them instead to train to join the Confederate Army.

St. Louis, though, was a Union stronghold, with a large stash of arms in its arsenal. Gov. Jackson was eager for access to the munitions stored there and worried that the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department would turn against the Confederacy. Consequently, he pushed through legislation that put an appointed board in charge of the Police Department, and promptly named five secessionists as its members.

- January 3, 1861 - Claiborne Fox Jackson is sworn in as the 15th governor of Missouri.

- February 26, 1861 - Senator Joseph O’Neil of the 29th District introduces “An Act Creating a Board of Police Commissioners and Authorizing the Appointment of a Police Force for the City of St. Louis.”

- March 2, 1861 - Receives initial and final approval in the Missouri Senate. The vote is 24-8.

- March 22, 1861 - Receives first and second readings in the Missouri House, and is referred to the St. Louis delegation.

- March 25, 1861 - Receives final approval in the Missouri House. The vote is 50-32.

- March 26, 1861 - The Missouri Senate agrees to the changes made by state representatives

- March 27, 1861 - Gov. Jackson signs the measure into law

The Civil War ended in 1865, but control of the SLMPD would remain with the state-appointed board for another 152 years.

Over that century and a half, state lawmakers representing St. Louis tried time and time again to give control of the department back to the city’s mayor and the Board of Aldermen. Every time, the efforts fell short. The closest the General Assembly ever came was in 2011, when so-called “local control” legislation passed the State House, but failed on the final day of the session in the state Senate.

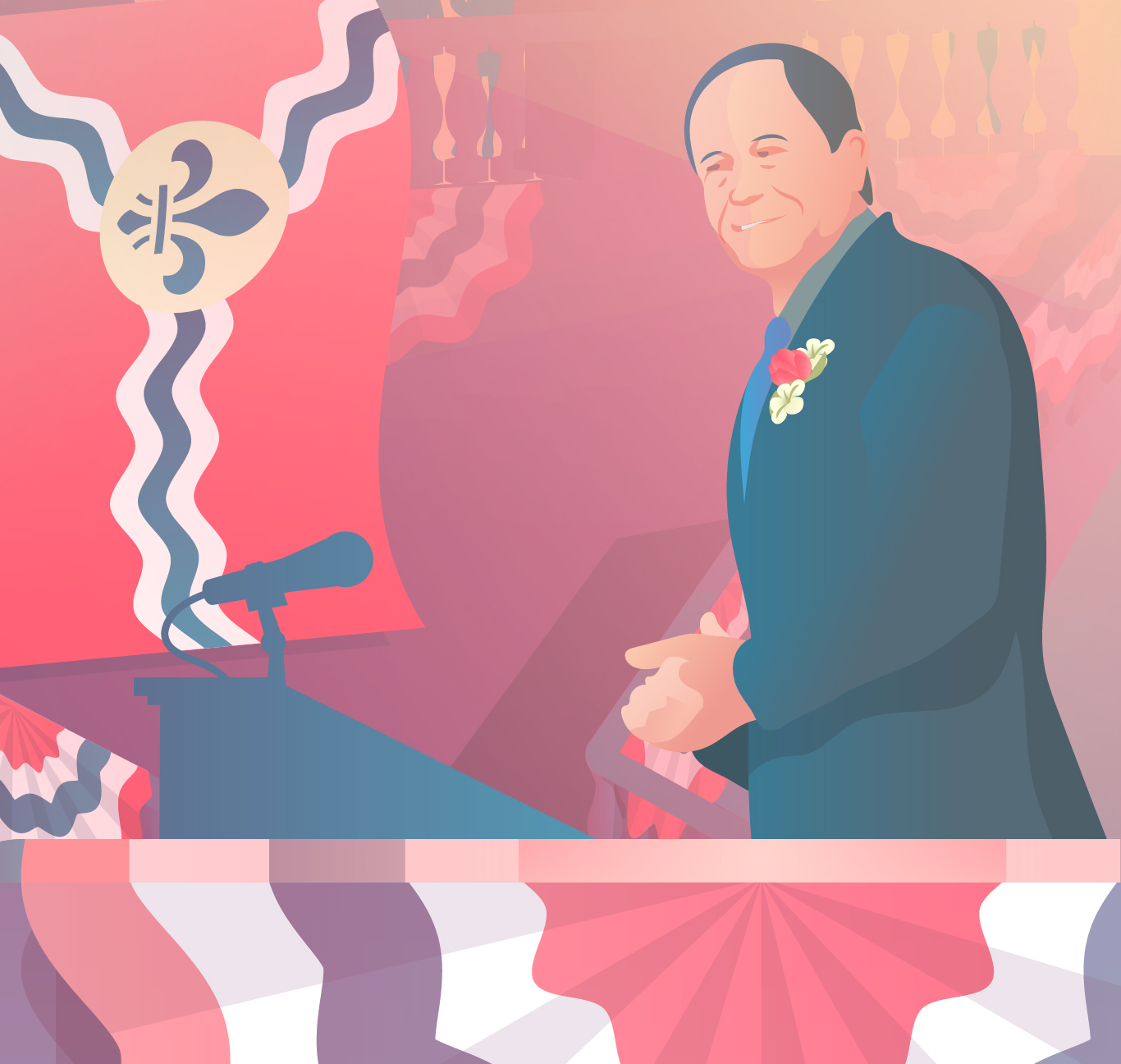

The failure of the General Assembly to act meant the issue went to the voters statewide, thanks to a petition drive by billionaire investor Rex Sinquefield. It passed by a wide margin on Nov. 6, 2012. On Aug. 31, 2013, Mayor Francis Slay signed an executive order accepting oversight of the department and ending 152 years, five months and four days of state control.

Crime in the city of St. Louis

In the 16 years that Slay was in office, overall crime in the city trended mostly downward.

Overall, more serious crime has dropped by more than half since 2001.

But those numbers include everything from license plate tab theft to murder. A closer look at the data reveals that overall decrease in crime has been driven by sharp drops in property crime. Changes in the way the department counted certain crimes also contributed.

Violent crime — murders, rapes, robberies and aggravated assaults — is also down, but not nearly as sharply, and the numbers move all over the place from year to year. The same is true for homicides, which over the last two years have reached levels not seen since 1995.

Three decades of declines in crime…

Loading...

… but murders on the rise

Loading...

Differing approaches to fighting crime

The mayor has spoken often of taking a targeted approach to crime-fighting based on evidence and technology. In the early years, it was targeting specific people, the “worst of the worst,” those committing the most crimes and whose arrests would therefore have the most impact.

The strategy of targeting specific people evolved in 2012 into the Homicide Deterrence Initiative, where then-Chief Daniel Isom moved officers from the day shift to the night shift, and put them in neighborhoods across the city to target gun crimes.

The deterrence program was a success — though crime was going down across the city, it went down faster in the targeted areas. And that led to multiple rounds of hotspot policing in 2013, 2014 and 2015. Rather than targeting specific individuals, hotspot policing flooded neighborhoods that were experiencing a spike in crime with extra officers, sometimes more than doubling manpower in a particular area. Slay made sure to follow up enforcement with city services like building demolition.

Hotspot policing evolved into the PIER (Prevention, Intervention, Enforcement and Re-entry) plan, which was developed over the course of a particularly violent 2015 and introduced that December. Fifteen of the city’s most troubled neighborhoods would receive intense attention from City Hall:

“In those neighborhoods, specially-tasked police officers and park rangers will work closely with building and health inspectors, streets and refuse workers, neighborhood stabilization officers, foresters, jobs trainers, firefighters, transportation planners, economic development officials, probation and parole officers, mental health practitioners, sustainability officials, and those who work with young children and school-age youngsters.”

The plan also called for cameras to be placed in those neighborhoods first, and for the city to hire more officers.

It’s too soon to judge the long-term success of the PIER plan. This year, Slay said 2016 data show crime went down in 10 of the 15 targeted neighborhoods. But aldermen and residents in those neighborhoods say there’s been turnover in the liaison officers. The department also remains understaffed, with measures to fund additional positions stalling in 2016 and not being introduced in 2017.