Mayor Francis Slay took the call in his office.

The head of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Robert Cardillo, was letting him know that St. Louis was the preferred site for a new, $1.75 billion facility.

“Yesterday was without question one of the best calls I’ve ever received as mayor,” Slay said the next day at a crowded news conference.

Earning the NGA deal wasn’t a solo effort. Joining the mayor behind the podium were lots of elected officials, both Democrats and Republicans from the city and state to Missouri’s Congressional members.

“It is a win for regionalism,” said U.S. Rep. Ann Wagner, a Republican from Ballwin. “As I look around at this group of people, coming together on behalf of the greater St. Louis metropolitan region, that is what has been key to the success.”

The Missouri state legislature, with a large Republican majority, made $131 million available to the city to help prepare the site. Perhaps more importantly, St. Louis County Executive Steve Stenger threw his support to the city’s north-side site, despite having two locations in the county also under consideration.

Regionalism

“I think one of the things Mayor Slay really recognized is that the economy doesn’t respect political boundaries and if you work together as a team you’re more likely to garner that new investment, particularly from companies looking at us from outside,” Denny Coleman said.

Coleman headed the St. Louis County Economic Council for 23 years. Then in 2013, he became executive director of the St. Louis Economic Development Partnership; a new combination of the city and county economic development offices.

He said the good relations between Slay, first with St. Louis County Executive Buzz Westfall, and later Charlie Dooley, paved the way for merging the offices.

“They got along so well that it gave the opportunity for the economic development organizations in the city and county respectively to do more and more things together,” he said. “As we did those, it became obvious that there were things we could do better if we joined forces.”

Those initial projects included putting in companion bids for casinos that resulted in the River City Casino in south St. Louis County and Lumière on the city’s riverfront. The city also allowed land it owned near St. Louis Lambert International Airport to be used for the NorthPark development, where Express Scripts is located.

“He’s done an extraordinary job of actually bringing people to the table and working with other elected leaders,” said Joe Reagan, president and CEO of the St. Louis Regional Chamber of Commerce.

Reagan said the NGA’s decision to open a facility in north St. Louis will be a major part of the mayor’s legacy. But he said Slay’s ability to work with others across state and county lines also helped bring the Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge to fruition.

That relationship-building is especially important, Reagan noted, because the city, at least geographically and population-wise, is a small part of the region.

City population

St. Louis had more than 856,000 people when it hit its peak population in 1950, then suffered a decades-long decline.

Mayor Francis Slay had hoped to turn the tide, but didn’t.

In 2000 the U.S. Census Bureau found there were about 348,000 people in the city, a 12% drop from 1990. Ten years later hopes were high that St. Louis finally would see an increase. Things looked optimistic, especially after the U.S. Census’ 2009 estimate that the city had 356,000 residents. But the final survey showed just over 319,000 residents in 2010, an 8% loss over 10 years.

It was a bitter disappointment for Slay, as he commented on his blog the day the results were released.

This is absolutely bad news. We had thought, given many of the other positive trends, that 50 years of population losses had finally reversed direction. Instead, by the measure of Census to Census, they continue, though at a slower pace. Combined with the news from St. Louis County, I believe that this will require an urgent and thorough rethinking of how we do almost everything. If this doesn’t jump-start regional thinking, nothing will.

St. Louis County also lost about 2% of its population from 2000 to 2010, dropping below 1 million people.

St. Louis population

Loading...

A couple of years later both Slay and St. Louis County Executive Charlie Dooley took note of a study done by Jack Strauss, a Saint Louis University professor, regarding the region’s foreign-born population. The study found St. Louis lagged far behind other regions in attracting immigrants, and argued that was hurting the region’s economic growth.

The two executives developed a task force and the following year the St. Louis Mosaic Project was born. The goal was to make St. Louis the fastest-growing region for foreign-born residents by 2020. Executive Director Betsy Cohen said the mayor has gone above and beyond to help attract and keep immigrants.

“He has been 110% committed,” Cohen said.

In 2015 the region hit its goal, increasing its small population of 4.5% foreign-born residents faster than any other metropolitan area.

“That means the work with all the partners, the city, the county, all the partners on our steering committee, is working,” she said.

Cohen said more work will need to be done, especially in light of the U.S. Census Bureau’s latest population estimate that puts the city at about 311,000 residents, about 8,000 fewer than in 2010.

The city’s plan for the future

Does the city have an overall planning document for its future? The answer depends on whom you ask.

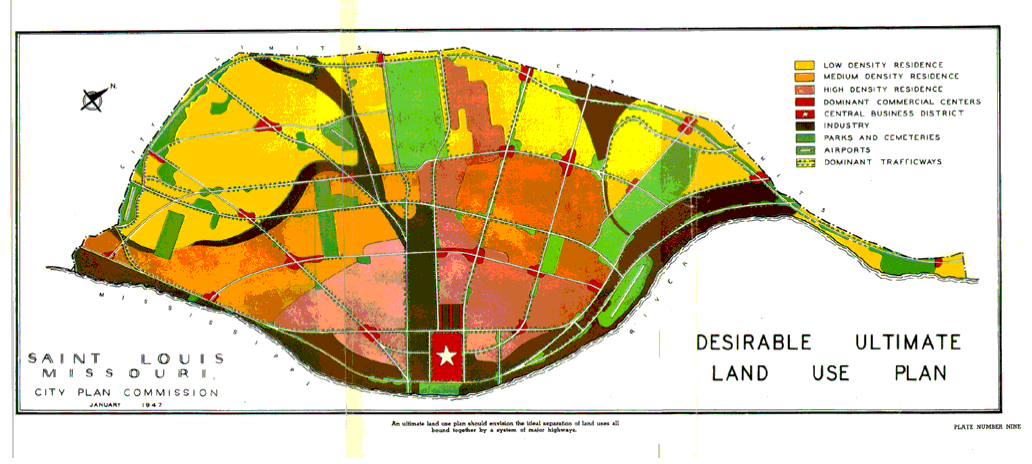

Sarah Coffin, a Saint Louis University urban planning professor, said the last Comprehensive Plan for the city was approved in 1947. Efforts in the 1970s and early 2000s to prepare a new plan faltered. That’s made it difficult for city officials to share with developers just what they’re hoping to attract, according to Coffin.

“There’s no indication and no vision of St. Louis to the rest of the region, and the rest of the country and the rest of the world,” she said.

That simply isn’t the case, said Barb Geisman, who served as Slay’s deputy mayor for development from 2001-2010.

“When Mayor Slay took office, one of the glaring holes in the city’s development fabric was the fact that there really was no plan,” she said. “So we embarked on doing this Strategic Land Use Plan.”

The administration sat down with each aldermen and then-planning director, Ron Stanley. Geisman said they were encouraged “to have vision, but also be practical.” The resulting document identified places that should be preserved, areas that might be available for opportunities, and districts that should have a mix of uses.

The Planning Commission approved the document in 2005. Geisman said the Strategic Land Use Plan is used as a “barometer” of whether a proposal should move forward or not.

Michael Allen, a preservationist and local historian, said while the 2005 plan replaced the land use aspects of the 1947 plan, it can’t be considered comprehensive. He points to the city’s website, which calls the 1947 plan the “last formally adopted general plan for the City of St. Louis.” The more recent plan was passed by the Planning Commission, not the the Board of Aldermen.

“Which means it is an administrative policy and not a public law,” Allen said. “There’s a big difference.”

A comprehensive plan also should include the city’s intentions for transportation, recreation, housing, not just land uses, Allen said. In his view, the lack of plan ultimately meant Slay’s economic development efforts were driven by the market, not the city.

“The administration has waited for private developers, companies, and investors to bring ideas to the city and then the city sort of decides which ones get the backing and which ones don’t,” Allen said. “It’s not been a visionary stance.”

But he said such a plan is likely to cost around $1 million if done professionally, something for which the cash-strapped city likely won’t have much of an appetite, even with a new mayor.